iToBoS is aiming to streamline melanoma diagnosis, but what happens once you are diagnosed with melanoma?

There are differences based on where you live, but the overall methods of treatment are the same. Here we’ll discuss treatment in the European Union and in Australia, where melanoma is particularly common.

Once your doctor identifies a spot that could be a melanoma, it will be cut out (excised) and sent to a pathologist for investigation under a microscope. They will generate a report describing the melanoma in detail so your doctor knows what to do next.

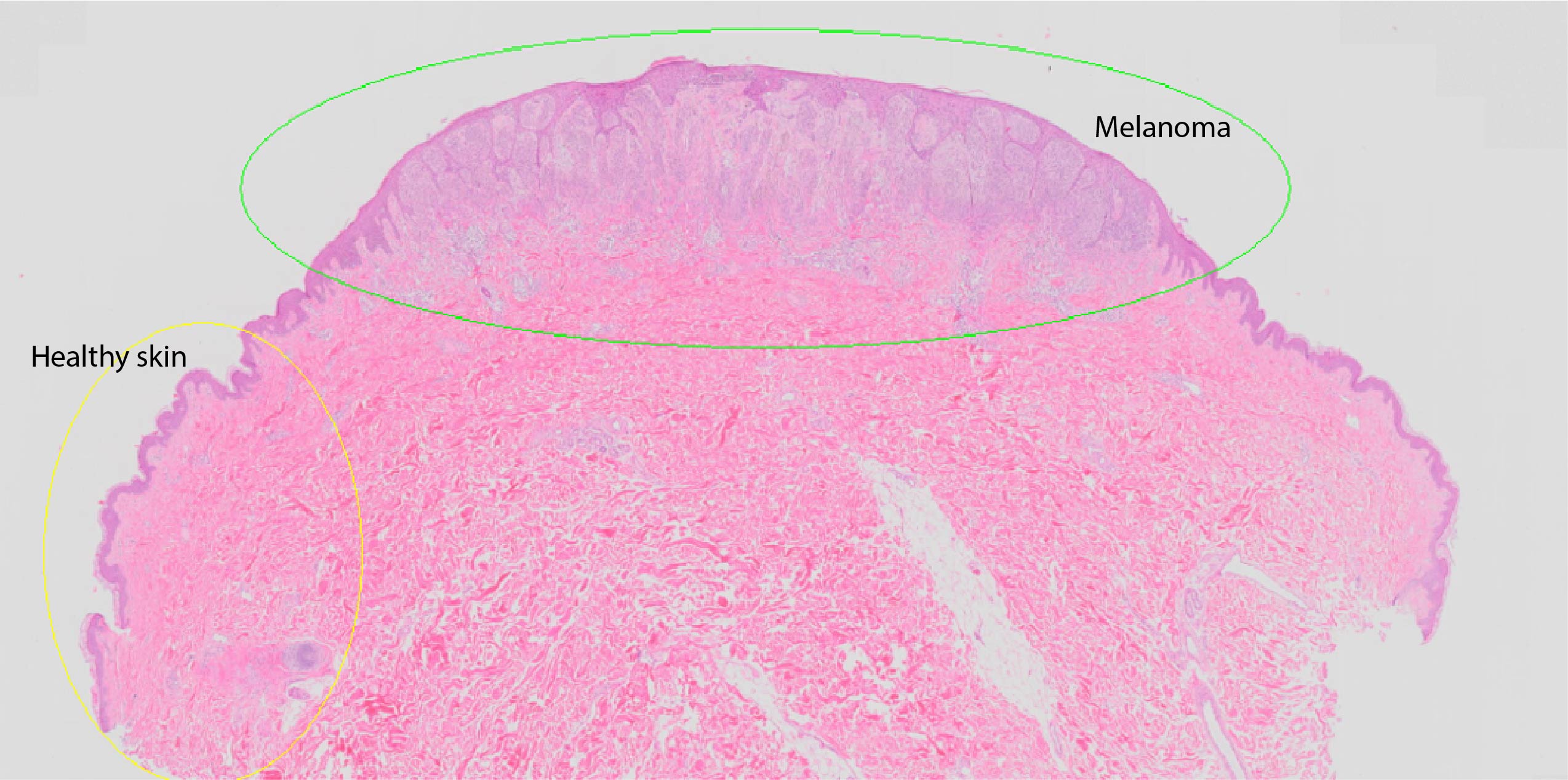

Image: histopathologists will look at sections of the melanoma like this one to gather information.

The most important detail is the thickness, measuring the melanoma from the skin surface to its deepest edge in millimetres. Over 1 mm thick is where your doctor will start to be much more concerned about your risk of spread. The report will also tell your doctor whether the melanoma was near a blood vessel or nerve, was ulcerated, or invaded by immune cells.

If your melanoma is less than 1 mm thick, the next step is removing more skin around the original melanoma site, ranging from 5 mm up to 2 cm based on how thick the melanoma is. For most people with melanomas less than 1 mm thick, that’s the end of treatment, though your doctor may recommend regular skin checks. However, there are some details in the pathology report that can point to an increased risk of the melanoma spreading to the rest of the body.

If your melanoma is over 1 mm thick, or over 0.75 mm thick plus another high-risk feature, your doctor will discuss a sentinel lymph node biopsy. Melanoma cells that spread are first carried to the lymph nodes, a part of your immune system. If there is so much melanoma that a lump can be felt through the skin, then the whole group of lymph nodes will be surgically removed.

If there’s no palpable lump, you will have an injection containing a tiny dose of radioactive tracer dye into the melanoma site, so it will travel to the same lymph node for imaging with a nuclear medicine camera. This allows a surgeon to plan where to operate.

During the surgery, blue dye is injected into the melanoma site to stain the draining lymph node, so the surgeon can remove the correct node and leave all the others. They will also excise 1-2 cm more skin around the original melanoma site.

If the node has no melanoma cells, you won’t need any further treatments besides regular physical exams to monitor unexpected recurrences by checking for swelling at your lymph nodes. The doctor will also look for symptoms like unexplained weight loss, pain or fatigue and for new primary melanomas on the skin.

If there is a positive lymph node, you might be invited to participate in clinical trials with immunotherapy drugs. There will also be further investigations to check whether the melanoma has spread further. Often, a team covering different aspects of oncology will work together to make a personalised care plan.

These may include from ultrasound checks of other lymph nodes, PET/CT scans of the rest of the body, or even MRI scans of the brain. If there are metastases, you’ll work with the oncology team to discuss surgical removal and potential drug treatments.

Having one melanoma means you are at risk of having more in the future, so the final part of your treatment program will be regular skin checks. In the EU, this will usually be done by a dermatologist, but in Australia your general practitioner might do them, or refer you to a dermatologist or another GP who has specialised in skin cancer, because melanoma is so common there.

You will also learn to check your own skin between visits, so you can bring a new or changing lesion to your doctor’s attention early.